12 Feb Prayer, Fasting, and Charity: the orientation of Lent

On Wednesday, 17 February, people of faith all around the world will gather in churches to have someone mark a cross on their forehead with ash. As this happens they’ll hear the words “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you will return.” In that line we are reminded of our mortality. And so will begin the pilgrimage of Lent, the 40-day journey to Easter.[1]

One of the longer seasons in the Christian calendar, Lent has a well-established history. It leans into the tradition throughout Scripture of commemorating sacred events and marking seasons in order to impart, build, and maintain communal story, memory, and identity. This is the point of following the liturgical calendar year after year: we mark the times and seasons that are important to our story and identity as those who follow Christ.

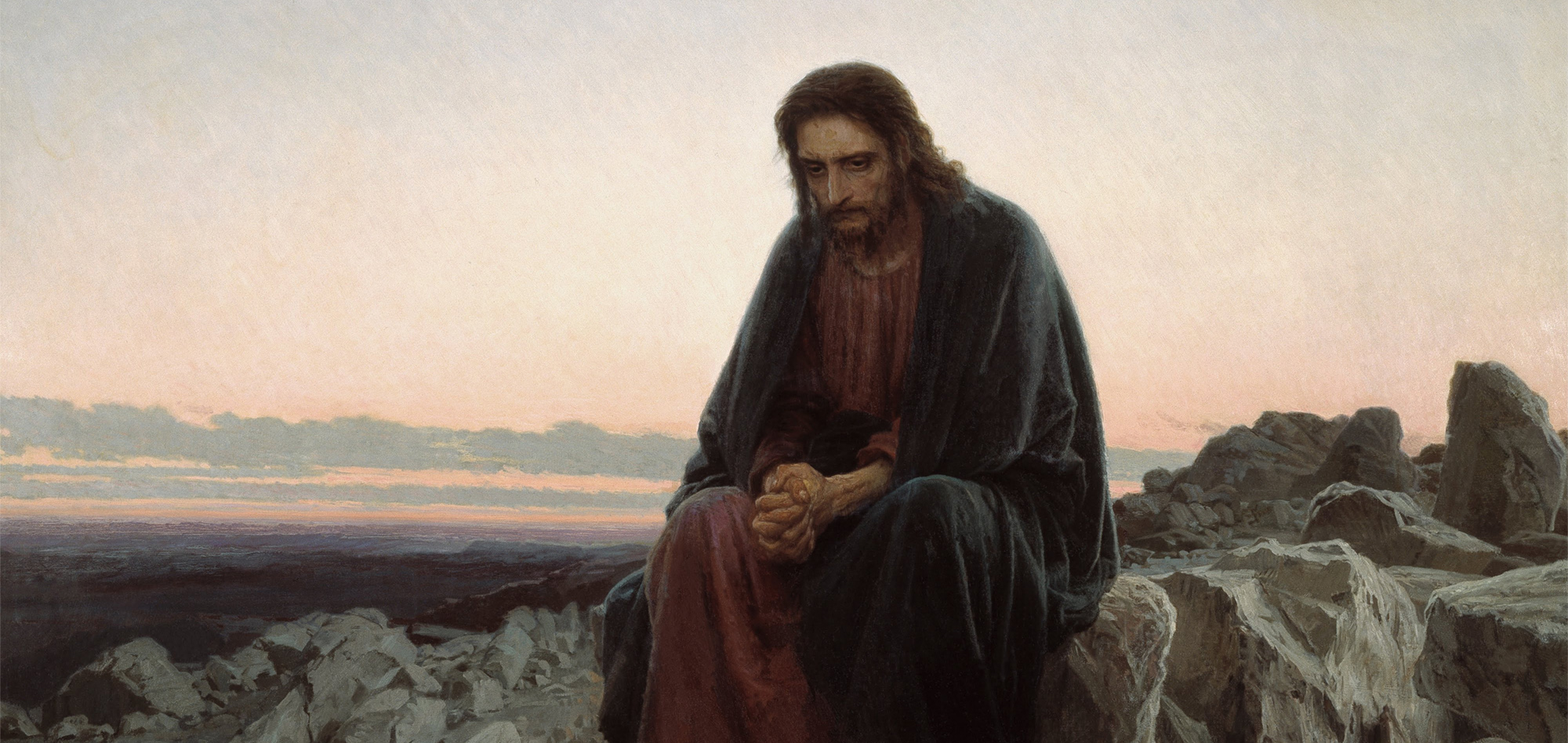

The origins of Lent are not clear, but the first references to it as a 40-day period of preparation occur in the teachings of the Council of Nicea in AD 325. It was adopted as a reflection of Jesus’ 40 days in the desert.[2] By the end of that century, a Lenten season of 40 days was widely accepted and practised. So as we engage in it this year, we are participating in a tradition that has existed for well over 1.5 millennia.

In its earliest days Lent was intimately connected to baptism, with baptisms traditionally occurring on Resurrection Sunday during Easter as an identification with the death and resurrection of Christ, as Paul explains in Romans 6. Lent was a time for baptismal candidates to prepare themselves for the receiving of the sacrament. After a while, those who were already baptised also entered into Lent as a way to join the candidates and to prepare themselves for Easter.

Over the years the actual practices of Lent have evolved and adjusted but the purpose remains the same: they call us back to the restoring work of God in creation and in our life together. The goal of our Christian life is union with God. Indeed, all of God’s activity within his creation is directed towards this end, and it is the purpose of everything we do with regards to our journey of faith. The ultimate outcome of this is captured in the wonderful word, shalom: being in right relationship among and with God, humanity, and creation. Images of the fullness of this are given to us in the closing chapters of Revelation. Seeking justice, seeking right relationship, describes the work that enables shalom to become a reality. Lent is a journey with this in mind; through its focus and practices, it realigns us with justice and shalom.

Within this frame we consider Lent’s three main practices: prayer, fasting, and charity. It is these three practices that form the foundation of our movement through Lent. In many church settings there are also traditional days and liturgies that contribute to the pilgrimage of Lent, but it is the practices of prayer, fasting, and charity that are common across all, though there may be variances in how they are practised.

Prayer, fasting, and charity are all nuanced, and their impact in shaping us multifaceted. Nevertheless, it’s worth considering the main ways they connect to the vision of shalom and open us to God’s salvific work. Understood this way, we can begin to see how they are healing and justice-soaked activities. As we consider prayer, fasting, and charity in the context of Lent, let’s talk of them as picking something up, putting something down, and giving something out.

Prayer

We often hear of prayer as conversation–and it is–but, at its heart, it is an act of submission and humility. It is an active orientation of ourselves towards the mind and heart of God. It consciously recognises something higher than ourselves. It stems from a desire, gifted by the Spirit, to place ourselves before God and to be shaped by him so that our lives become a vessel directed by, and reflective of, his will. In the image of shalom, therefore, the practice of prayer orientates us towards right relationship between God and ourselves.

With that in mind, as we undertake self-examination, ask yourself, when it comes to your rhythm of prayer through the season of Lent, what could you pick up?

Fasting

Fasting is the giving up of something for a defined period of time. As a spiritual discipline it is usually connected to food. In a consumer-driven culture where we are often defined and given status by what we consume and what we contribute for the consumption of others, fasting is a very powerful practice. It reminds us what hunger feels like. It breaks the hold that things have on our life. It gives us a chance to turn our attention away from what we consume and towards God. It seats our identity away from consumption. In the picture of shalom, fasting can be seen as a righting of our connection to ourselves; at the same time, such restoration does not happen in isolation from our relationship to God, others, and creation.

Older traditions around Lent come with prescribed fasts, but if exploring those doesn’t suit you, consider: what is there in your life that you could put down for the 40 days? It may be something that has a hold on your life. It may be something that is good but has taken a bigger place in your life than is needed. It may be something that is not an issue at all, but in giving it up for a time, you enable greater moments for your attention to turn towards God and others.

Charity

Traditionally, this is referred to as almsgiving. The focus of this is towards others and, yet, it can also be seen as a type of prayer and fasting. It is prayer insofar as giving to others in need is giving to Christ, and it is fasting because it calls us to give something up so that we can give to the life of another.

In relation to Lent, much conversation takes place around what we will give up (fasting), and there are many ways via our communal gatherings that we are drawn into prayer, but charity is too often only a side thought, if at all. Yet, without it, the vision of shalom remains incomplete. Charity turns our attention to how we relate to others and even to creation itself.

So, just as we have asked what we could pick up (prayer) and what we could put down (fasting), so here we ask what we could give out. As you journey into Lent, prayerfully ask: who is God calling me to give out to? What might this mean for my time, my money, and my shape of life in this season?

To increase our focus on these three areas this Lent, we turn to the “Sermon on the Mount” found in Matthew 6:1-8. Here we find charity, prayer, and fasting placed together as tangible activities of the Christian life.

1“Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them. If you do, you will have no reward from your Father in heaven.

2“So when you give to the needy, do not announce it with trumpets, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and on the streets, to be honored by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. 3 But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, 4 so that your giving may be in secret. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.

5 “And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners to be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. 6 But when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you. 7 And when you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words. 8 Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him.”

Matthew 6:1-8

Prayer, fasting, and charity are mainstays of the Christian life. They’re encouraged all year round, but with life grabbing our attention and providing so many distractions, Lent provides a great opportunity to examine their place in our life and to give them extra attention as we prepare ourselves to honour the gift that changed everything–the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ.

Finally, it is this gift—the saving work of God—that occasions our Lenten journey. So, allow me to offer an encouragement. There’s a high chance we will make some good commitments for Lent, but have moments where we trip and stumble in our fulfilment of them. That stumbling is no reason to stop, but I like to talk about how a failed Lent is a worthy Lent. Why? Because it reminds us that the real gift is what Jesus did on that cross and what was achieved in that empty tomb. That had nothing to do with us. Lent isn’t about us saving the universe; that’s what God is in the business of accomplishing through Christ. Lent is about us remembering and returning to the grace, mercy, forgiveness, and reconciliation he has freely given. If it takes a failed Lent to remind us that he’s got this, then so be it.

[1] There are variations around when it ends. For the Roman Catholic Church it ends on the Thursday of Holy Week (the week leading into Easter), while others, including myself, end it on Easter Saturday. There is also variation around whether the fasting of Lent includes the Sundays as Sundays are a celebration of the Resurrection. I do not include them. Either way the Sundays are still significant. Of course, for number buffs, when it ends and whether or not the Sundays are included will change the number of days, but, traditionally, it is seen as a 40-day period.

[2] Matthew 4:1-2; Mark 1:12-13; Luke 4:1-2

(Image: “Christ in the Desert,” Ivan Kramskoi, Public Domain)