27 Mar A Strange Kind of Blessing

This piece first appeared on the blog Imagining Otherwise, written by Venn Senior Teaching Fellow Andrew Shamy, and has been reposted here with permission.

I’ve been dreaming of line graphs. The perilous upward snaking of them; the longed for levelling off.

My phone tells me my screen-time is up 9% on last week; it was up 15% the week before that. I’ve looped a video of an Italian priest accidentally enabling filters while live-streaming Mass (the star-fighter helmet was my favourite, followed by the joyous sprinkles of light), but I don’t think this explains the increase. My compulsive reading of the news may.

I received 100 messages in a 15-minute window from one WhatsApp group: prayer requests, explainer videos, Italian priests, advice on home-schooling children, news of a friend in a hospital in Berlin struggling to breathe.

These are difficult days. We are unsettled and afraid. COVID-19 has consumed us all.

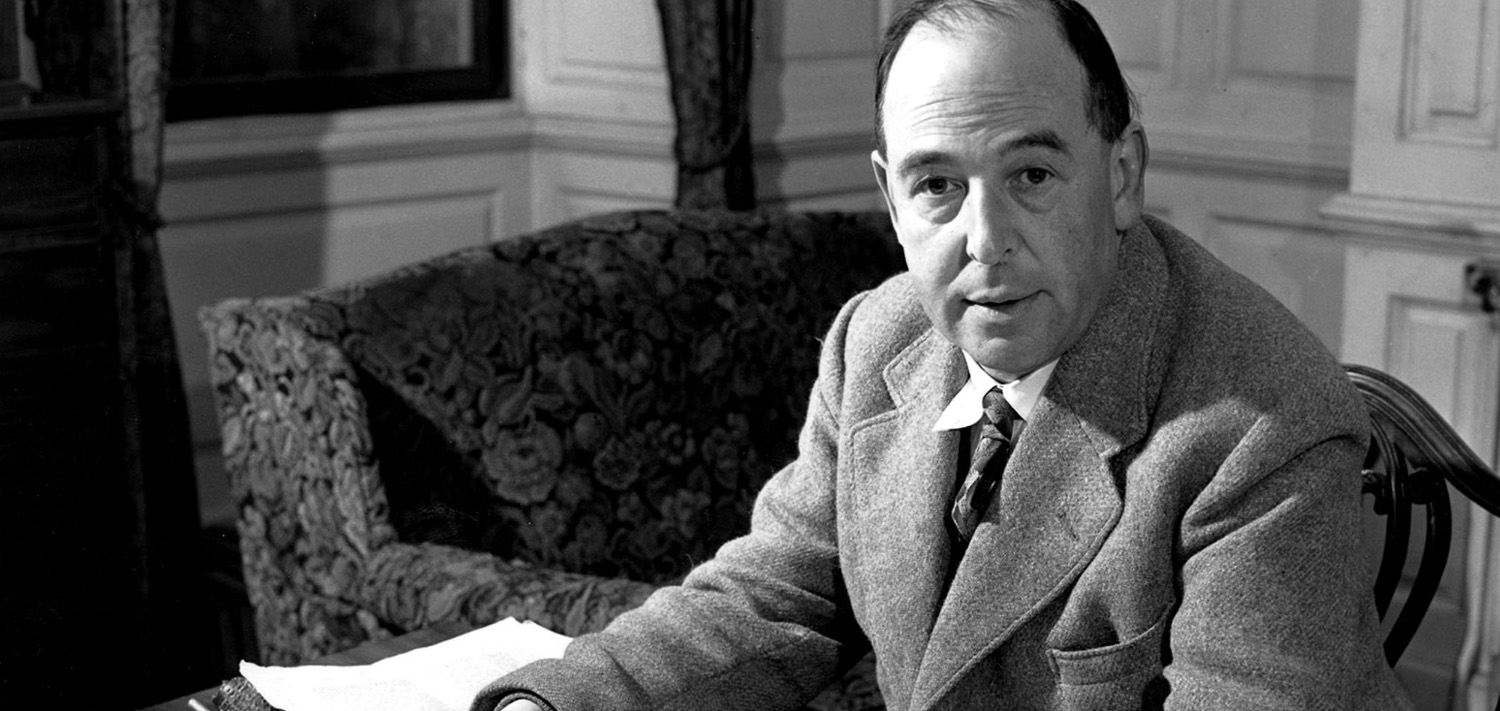

I’ve found myself re-reading a sermon by C.S. Lewis called “Learning in War-Time.” It was preached on October 22, 1939 at St. Mary the Virgin Church, Oxford, to an audience of university students and dons. War World II had broken out a mere seven weeks earlier and Lewis’s words offer wisdom and encouragement to those seeking to live well in a time of crisis.

Lewis makes a number of helpful points, but here I wish to focus on just one. As he so often does, Lewis offers us perspective. For him, “the war creates no absolutely new situation: it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it.” “Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice.” “Cries, alarms, difficulties, emergencies,” are normal conditions, the war has simply aggravated them. More, human life always takes place in the context of great drama. As creatures, at every moment we are advancing toward eternal realities—for Lewis, either heaven or hell. We have always lived “under the shadow of these eternal issues”. War or pandemic do not make life more dramatic, more filled with serious consequence and risk, they simply make these realities more viscerally felt.

There is wisdom here for us. It is perhaps a peculiar risk of modern life (at least, it was) that many of us can live for long stretches insulated from any real struggle or harm. We expect and demand comfort and control, freedom to do as we please, because this is what we’ve grown to expect. We are at best only dimly aware (and only then in a kind of abstract and theoretical way) of our reliance on God, and we are confident in our abilities to get on and get things done.

To us, COVID-19 comes as a rude shock. But by aggravating and revealing truths of human life and humans plans we prefer to ignore—their fragility, susceptibility to disruption and trauma, their performance under the shadow of eternity—this pandemic provides an opportunity for reflection, perhaps even re-evaluation.

As Lewis concludes his sermon:

“All the animal life in us, all schemes of happiness that centred in this world, were always doomed to a final frustration. In ordinary times only a wise man can realise it. Now the stupidest of us know. We see unmistakable the sort of universe in which we have all along been living, and must come to terms with it. If we had foolish un-Christian hopes about human culture, they are now shattered. If we thought we were building up a heaven on earth, if we looked for something that would turn the present world from a place of pilgrimage into a permanent city satisfying the soul of man, we are disillusioned, and not a moment too soon.”

This is sobering. But Lewis can be mis-heard here. We are not to understand him as calling the students and scholars gathered on the scratchy wooden pews that morning under the grey spires of Oxford University to give up learning; or, for us to abandon ordinary human goods and pleasures—of learning, but also beauty, laughing, cleaning, gardening, cooking, and so on.

For Lewis and for the Great Tradition out of which he speaks, God has given us appetites for truth, beauty, and goodness—and this is a sign that they “have proper function in God’s schema.” The problem is not the enjoyment of earthly goods and pursuits, but when these do not take their proper place. “We are to do all these things to the glory of God,” Lewis reminds us, quoting the Apostle Paul. All earthly goods are given by God to be enjoyed, but only as second things, not first or ultimate things. “Christianity does not simply replace our natural life and substitute a new one: it is rather a new organisation” of natural life. We are to live toward God and toward all things in relation to God.

We are in the midst of an apocalyptic moment. The Greek word Apocalypse (ἀποκάλυψις) means “revelation”, an unveiling of things hidden. COVID-19 is revelatory. It makes evident what has always been the case: the fragility of human life and plans; the impermanence of earthly goods; the inevitability of death. Both as individuals and as a society we are prompted by our fears and the disruption of our ordinary ways to ask, what is being revealed to us about our goals, desires, expectations, hopes, comforts, beliefs, securities, and how well these attend to the world as it really is?

The current crisis is an opportunity to consider what it is we have been relying on, to evaluate the order of our loves, and to confess where we have put things other than God first. This is not to say that COVID-19 is good, or should not be fought with all our God-given courage and ingenuity, but it is an opportunity, a species of God’s habit of bringing good even out of chaos and death.

And I suspect one of those goods is this video of an Italian priest live-streaming Mass.