24 Feb Field Notes: Alistair Reese

Tell us about your family and upbringing?

I was raised in Hamilton. My father was a plumber, and he also had his own business. My parents sent me to a private Anglican school from the time I was seven years old until the time I left school, when I was 17, 18. So that was very formative.

In a good way?

Well, a mixture! We had a good family life. The rest of my dad’s family were rural, so we had quite a strong rural influence—which probably had some bearing on what I ended up doing later in life. I spent a lot of time on farms. But, most of the time I was at school, six days a week. In those days, we had school on Saturday mornings.

What was the place of faith in your life growing up?

When people ask me about my faith journey, there are two aspects to it. First, there was my childhood faith journey. We went to chapel every day—formal chapel—where we had a minister, hymns, prayers, Bible reading, etc. I was confirmed when I was 13. I’m sure that played some role in how I saw things. However, I wasn’t raised Christian, and my family were completely secular. My grandfather and my father were probably avowedly atheistic, so I can’t quite work out why I got sent to those schools, to be honest—it’s quite providential.

And what were the significant formative aspects for your faith after leaving school?

When I left high school, I went to Waikato University for a year, mainly because I didn’t know what else to do. I was interested really in two things in life at that stage: one was sport, and the other one was music. In the end, I think the music captured me. I became very enamored with the narrative of the time, which was the cultural revolution of the mid-to-late ’60s. Even though I had been to church or chapel every day, as soon as I left school, that was the end of it. Somehow, the faith wasn’t motivating, and I began to explore other realities.

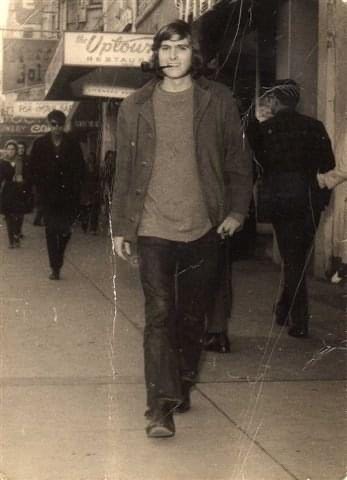

I actually dropped out of university after one year and went overseas. I spent almost 10 years as a peripatetic wanderer, you could call it. I went straight from New Zealand to North America. One of the things that drew me was the beat poets, the hippie revolution, protest movements, and all that. So, that was my first port of call. I call it drugs, sex, and rock and roll. That was me for quite a long time. I also did a lot of reading—reading was my other passion. That eventually led to reading around spiritual stuff—anything other than Christianity.

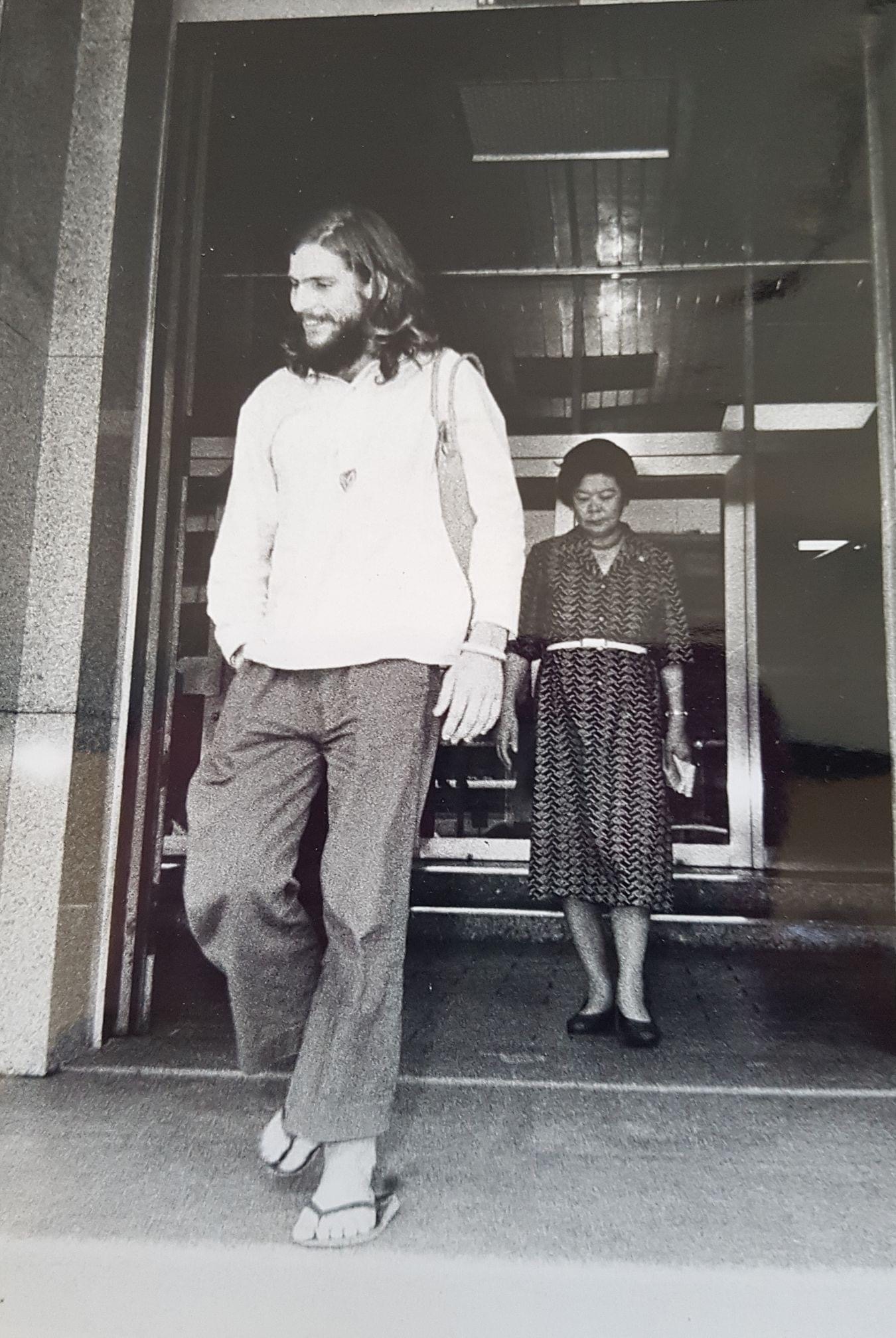

During the midst of those 10 years, I was quite involved in what we would call the protest movement. At one juncture, I was on an anti-nuclear boat for a couple of years, and we sailed through the Pacific. We sailed all the way through to Japan and China. I met quite a few interesting spiritual people on that journey. Some of them were political Christians that were involved in the peace movement, along with some Buddhists. So, the spiritual aspect of life became quite interesting and became quite strong for me, even amid that wandering.

I’m sure there are probably lots of different things, but would you name one person, or instance, or book that was pivotal in your turning back to Christianity?

Yeah, Bob Dylan. When I was back in New Zealand, I was a musician. I worked in restaurants, and I also did odd jobs painting houses. Bob Dylan put out his album Slow Train Coming—he’d just been converted. I remember when I first heard about this, I thought, “oh no, not him too!” because there were quite a few of my friends around that time who were being converted. They were radical conversions as well because the lifestyle that we were leaving was quite anti-Christian. Anyway, listening to Slow Train Coming over and over again on the building sites really undid me.

That was the first one. I’ll just mention one other that was quite significant. At this time, I started entering into te ao Māori, and I went to Parihaka. When I was there, the Kuia referred to the whakatauki—“glory to God, peace on earth, and goodwill to all mankind.” So here I was, this alternative person who was seeking truth in every area other than Christianity, falling in love with te ao Māori, and then being confronted with the reality that Te Paipera Tapu actually wasn’t such a bad thing after all. So, it was Bob Dylan and those folk within te ao Māori—and then these other conversions of my friends—who all helped soften my heart to the extent where I at least had to turn and consider the truth claims of Jesus.

Tell me about Jeannie.

As I mentioned, I’d come back from overseas—I’d had an accident in England, and I had to recuperate. Otherwise, I probably would never have come back. I was at a music festival just a week or two after returning, and I was on crutches. Jeannie was living in a little village called Waikino, which is just beside Waihi. Some friends of hers ran a café and, on that day, had asked her to help them out because of all the traffic coming in from the festival. Long story short, I went in, ordered a cup of coffee, and Jeannie served me. That began a long journey of relating to each other. Jeannie wasn’t a Christian at the time, but, shortly after that, she went back to Canada and became a Christian and began to talk to me about this conversion experience. She was deeply New Age—she owned one of the first and largest mail-order occult bookshops in New Zealand, called Sunshine Books. We joined together around a variety of Eastern mystic beliefs. When she went off and got converted, that was another piece of my foundation [for not believing] cut away from me. She ended up returning to New Zealand and went to a Bible college. I was invited down to this little community in Paengaroa, in the Bay of Plenty, where she was living after being at Bible College. That’s where I encountered the Holy Spirit full on and became convinced that the claims of Jesus were true. I began to follow him from then. That was in 1979.

Let’s come to the question of putting down roots and raising your family in Te Puke.

When I became converted—when I met the Holy Spirit—it was in the Bay of Plenty, and I was living in Auckland. Immediately, I moved from Auckland. As I said to you before, I was living a very peripatetic lifestyle and playing rock and roll. I’d never had a proper job. Then, I became a Christian, so I had to tidy myself up! I got a job—I became a house painter—and Jeannie and I got married. After about a year, I felt God say “buy a field.” So, a group of us ended up buying a farm, and that’s how I became a farmer. We’ve lived on that farm ever since. We raised our two children and established a Christian school on that farm. That’s where the kids were nurtured and raised. They used to help out on the farm and then just wander down the hill to school.

Once you settled there, was your main occupation as a farmer?

Well, that was what it was meant to be. But I was also involved with leading the church, and founding the school and getting all that going. I’d never farmed before—that was a big learning curve. That was where we made our living. I was probably a very poor farmer because I had so many other things on! I’d come home from the cowshed, take off my overalls, and whip down to the school to take devotions, and then preach on Sundays, and all that sort of stuff—a bit overcommitted. My heart was always more in what in those days we called ministry. I don’t see it quite the same way now, but that was where my heart was. Even though I loved the farm, I was probably a frustrated farmer in that way.

Are you still living there?

Yes, we’re still there. A big change happened around the year 2000. Just prior to that, I’d started learning te reo Māori formally and doing some papers at university, even though I was also farming and pastoring the church. But, in the year 2000, we got an opportunity to convert most of the farm to kiwifruit. We stopped milking the cows, and we planted a large area in kiwifruit. A company did that work for us, and we were able to lease the land out, so I was released from day-to-day farm work. I was still doing the administration and the leadership of it, but I wasn’t hands on. I enrolled to go back to university. The first courses I did were in Waikato and Tauranga; then, I went to Hamilton. That started the journey of my academic pursuits while still living on the farm and looking after it.

Years earlier, would you ever have thought that you would go on this academic journey?

Well, I never thought I’d have gone on a farming journey—or an academic journey! As I said, I’ve always been a reader. But, in my early years, I was converted into a revivalist Pentecostal background, and academic things were very frowned upon. You were told that academia was just the head, and you really need to stick with the “heart stuff.” Any inclination to the academic world was discouraged, and, as it was, the world of te ao Māori was the same. It took me a little while to break out of that influence. I owe a bit to some people who helped me break out of that mould.

The central theme of this issue of Common Ground is the question of hope. How have you cultivated hope in the face of some of the challenges you’ve faced?

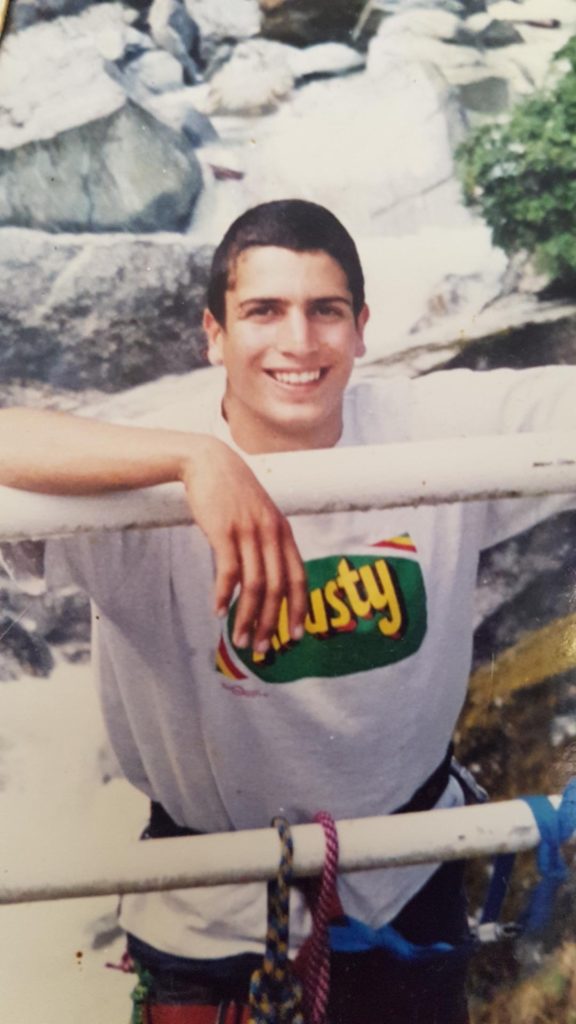

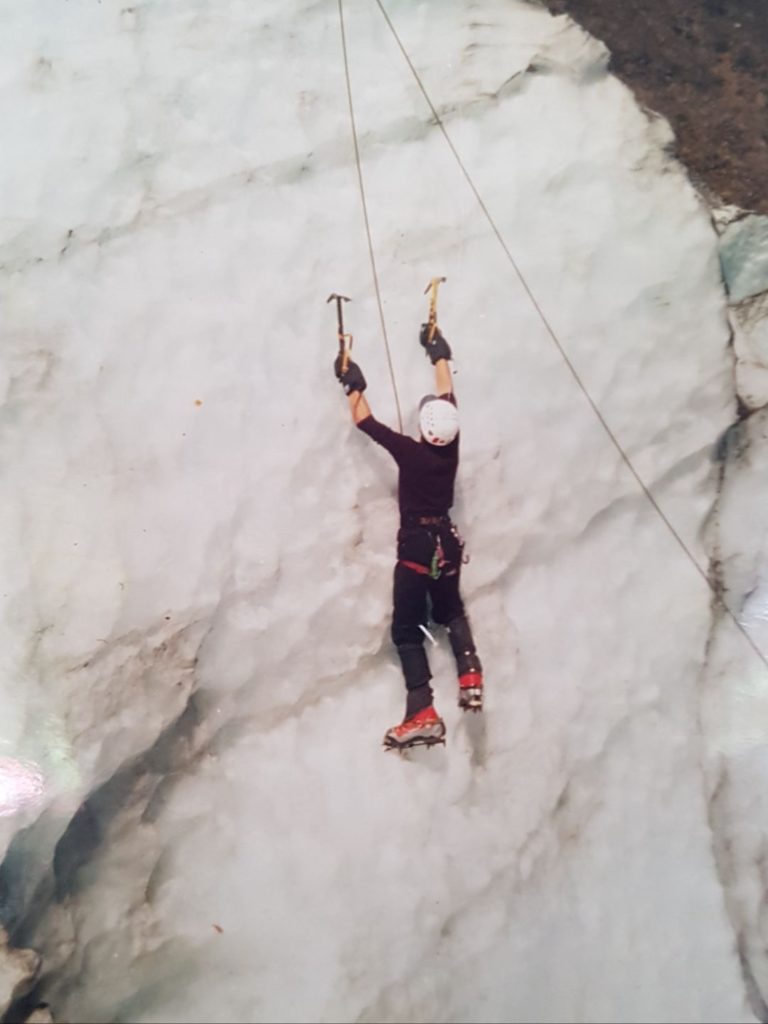

Probably the greatest crisis of hope was the loss of our son, Sean, in an avalanche. He was 18 years old at the time. I think that was my first real major crisis in life; both Jeannie and I had to work through that. One of the things I’ve learned is that we’re all individuals in the way we deal with crises. When Sean died, there were two main things that helped me at the time. One was that I had a theology that stuff happens in life: I wasn’t a triumphalist. Of course, I was shattered but not surprised. Tom Wright has written a book called Surprised by Hope. I think you could sometimes change this to “Surprised by Crisis.” It does happen, and it did for us in the year 2000—more than 20 years ago now. The first thing for me was actually having space in my “God world” that things like this can happen. I didn’t need to make a paradigm shift.

The other thing—as a musician, you might understand this Jannah—is that I found a great solace in worship. I left a lot of the “mind stuff” to the side—the “working it out” stuff. And I’d just weep and weep in his presence while people were worshipping. Sometimes, I wouldn’t even sing. But, in that place, I heard these whispers, and the whisper of God was like: “If you don’t know me here, you don’t really know me.” This is how I translated what I sensed was coming from God.

I wrote a passage called Lament for a Son, inspired by Nicholas Wolterstorff’s book of the same name. I’ve found great solace in being able to lament—and great catharsis. It wasn’t like the “hope-in-the-end” theology that some Christians gave to Jeannie and I, which was very counterproductive. They’d quote particular verses and say things like “he’s in a better place.” They didn’t seem to help a great deal. I think that being free and finding space to pursue your own journey in the midst of that pain—that’s what brought me out of any place of despair. And I think that’s hope. I think that lament changed me and the way I see the world, and probably the way I relate to other people. Te ao Māori has been able to understand that.

One of the things I remember Jeannie saying was this: “why don’t you just come and sit on the mourning bench with me.” We’d sit in the presence of God and, somehow, find solace in that without trying to work it all out. That produces a psychology of hope, I think.

We faced quite a different challenge—ten years ago now—when a kiwifruit disease was brought into the country. We had to physically cut out our whole orchard. We had a period of time when contractors would come, and there were just days and days of chainsawing the whole orchard. We lost the whole thing. I think that what happened with Sean prepared me again for this—that God is present in the midst of it. I love that verse, that he’s “a very present help in time of trouble” [Psalm 46:1]. This helps my imagination, and the imagination is a place where hope sits.

For me, there are two kinds of hope. There’s the hope that Hebrews talks about, which I call the “capital-H Hope,” and that’s the anchor of your soul. That’s the hope of Jesus that sits and resides as a Hope for eternity. Honestly, I don’t quite know how much that operates within my equilibrium because, as I said, the question of eternity and what’s going to happen is not something I worry about. But, intellectually, I assent to it. Then there’s what I would call the “lowercase-h hope.” I see that in the beautiful Psalm 27, where David says, “I’m convinced, I believe I’ll see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.” In the midst of this great mystery, in the vicissitudes of life and these great challenges that we all face from day to day, there’s a promise that somewhere, somehow—not just in the eternal realm—God in his sovereignty will come and show up in some ways.

I really appreciate the Isaiah saying, “How beautiful are the feet of them that bring good news” [Isaiah 52:7]. For example, over the kiwifruit disaster, I’d be looking for hope every day in the news: you know, the scientists are working on it; or the kiwifruit people are making progress; or, when we replanted, the plants are looking good. People bring good news. That’s become a very powerful motif—a motif of hope that people can be bearers of this good news. Now, I know that the ultimate good news is the reality of God and the coming of the Son. But, I think on a day-to-day basis, that kind of hope helps keep people going so they don’t become hope-less. Being hopeless has got to be one of the worst places to be living. We can find hope in the most unexpected places as someone bears some news. It can be nothing earth-shattering, but it could be something good.

The other thing that has been quite a strong theme over the years of trial and crisis has been Paul’s wisdom, where he says, “in all things, God works together for good for those that love Christ Jesus and are called according to His purpose” [Romans 8:28]. One of the things I’ve seen is that while the rain falls on the just and the unjust alike, and while being in Christ doesn’t spare you from life’s challenges, the sovereignty of God is able to work something for good in the midst of that. The big challenge with this is to find the right balance on the continuum between triumphalism and fatalism. A triumphalist perspective would say, well, I’m now a Christian and perhaps claim Psalm 91, and say that nothing bad is ever going to happen. But I don’t know anybody who is actually able to maintain that throughout their whole life. And the fatalist would say, “que sera, sera.” But here, you’re cast adrift. You’re on a sea of events. This other theme has given me great hope that God, in his sovereign capacity, is able to be weaving within my character. This doesn’t transgress his divinity in terms of his intervening, but something else is also going on. And that something is not just eternal with eternal consequences, but I believe it has present consequences as well. Those are some of the snippets of hope.

I wonder about the role of prayer in the conversation around triumphalism and fatalism. It strikes me that what you’ve described leaves room for dynamism in the intimacy of prayer because God does respond. We can’t always explain it, but it’s not nothing.

You’re right. And that’s something I didn’t say, which is that the term “prayer” is not quite big enough for me, but it’s how we relate to God in all this, whether it’s vocally, or in quietness, or in anger. For me, it’s the catharsis of that relationship in the midst of crisis. Also, a mysterious wellbeing can emerge out of the encounter, which we so often see in the Psalms: that as we pour out our heart, in whatever way, something happens. We are transformed, even in terms of the way that we relate to God. Thinking of Psalm 73, I remember as a young farmer reflecting on other farms near to us. We’ve done very well, and I’m very grateful for that. But I could never claim to be a great farmer. Yet, there are some farmers around us who are very secular and very performance-driven. They’re very good farmers, and their farms always look good. I remember looking over the fence and thinking of Psalm 73 where it says, “Surely God is good to Israel, to those who are pure in heart, but my feet slipped when I envied the life of the arrogant”! And I’m looking at their lives, and I’m struggling away here on my farm; I’ve hardly got a tractor that’ll go, and I’m looking at these guys who don’t even care for God, and the Psalmist talks about how I’ve become “a brute beast”… I’m raging around in this place! And then Psalm 73 again: “it all became clear to me when I came into the sanctuary of the Lord, and then I understood.” Well, the psalmist understood the eternal realm—but I love that place of “when I came into the presence, I understood.” So, going back to hope, I think that, as I said before, Christians have got to be careful of offering a hope that is too simple for people. Because actually, I believe that—that hope can be a bit like a mountain; it’s not something that is necessarily easily attainable. It is a struggle sometimes to enter into the space of hope.

That’s an interesting question, isn’t it? The question of a “discipline” of hope. There are some things, and you wonder, is it a gift, or a discipline, or both?

Yes, because to think of ourselves as receptors of hope, sometimes it can be more difficult for some of us to receive the hope. That’s perhaps where some of the discipline comes in—an exercise in hope where the heart remains soft.

Going back to your description of lament and of being in the presence of God—the great solace you found—I’m interested in your church community at the time. Did people understand your lamenting, give you room, or join you?

Yes, our church community over the years has had lots of ups and downs, and we’ve done a lot of things wrong, but, in that particular chapter, it was very, very gracious. At least for me, personally—I don’t want to speak for Jeannie in this—but I found that because we’re a very informal group, people were encouraged to respond to God in whatever way they wanted to. You’d have the dancers and the clappers and the shouters and, you know, whatever. So, the weepers were welcome as well. I know that, for a while, Jeannie didn’t go because she couldn’t find that safe space. But, for me, I could. It’s not a judgment either way. I’m not sure that we understood, necessarily, the psychology or the theology of grief, even at that time, because most of us were all young and hadn’t experienced anything like that. But I’m very grateful for that space.

What gives you most cause for hope in the church?

God. Yeah. Simply because, to be honest, if I put my focus anywhere else at the moment, I end up in a fairly despondent space. I mean, there’s beautiful people around. Beautiful people. I’m loving the work that you guys are doing at Venn. I think the community that you’re forming and working with—those are beautiful signs. But it’s short-term. You know, I wouldn’t want to put too much weight on you to be the answer. So, essentially, I just sit in that space, knowing that the Church belongs to God. And God has promised—in ways that we see, and in ways that we don’t see. His purposes stand firm through all generations.

A big question to end on: what is your hope for Pākehā and Māori as we move forward?

One of the metaphors that I use in terms of our relationship is that of the marriage—between Tangata Tiriti and Tangata Whenua—and the love that each of those have for one another. I know these are high ideals, but we’re talking about Kingdom of God ideals, in which we prefer the other and are looking for the highest good. So, the aspiration that I have is for the prosperity and restoration of Māori in the land and that we, as Pākehā, learn what it is to be in relationship with this work of the Holy Spirit. And I believe it is a work of the Holy Spirit—this work that God is doing worldwide with indigenous peoples. Our role is to yield and to cooperate because I believe it’ll be a real challenge to some of us going forward. Giving up some space—giving up some things that we haven’t even consciously taken ourselves—but that have been our birthright. I think the time is changing.

So, as Pākehā, to be able to find that space where we can really do that Philippians 2 work, where we say “even though being in the fullness of God [Christ] did not consider equality with God something to be grasped”. So that, somehow, by the Spirit, we can actually be drawn into what it means to yield our dominance in that way. I don’t want to get too political in terms of the terminology because I think it’s fundamentally a spiritual response to what God is doing by His Spirit—the restoration of a people who have been treated unjustly. This is something that the church could really show some leadership in—you know, “that which the locusts have eaten” [see Joel 2:25]. To see that happen would be a big hope.

(Images: Supplied by Alistair Reese and Venn Foundation, 2022)