20 Aug Field Notes: Sarah Askey

Sarah Askey is a Conservator for the National Library, specialising in books and paper. She works at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington. Sarah attended Venn’s Summer Offering, The Centre of All Things, in Wellington early 2021 and she has been attending SPACE evenings for the past two years. In this Field Notes interview, she spoke with John Dennison, reflecting on her career to date, on her current work with early printed Māori texts, and on what book conservation has taught her about God.

Tell us about yourself

Well, I never thought I would end up living in New Zealand. My Mum’s Canadian, my Dad’s a Kiwi, and I was born in the UK. We moved to NZ when I was six, and I grew up in Christchurch. I went back to the UK to study book conservation and expected I would have to stay there to find work, and I was quite happy with not ever coming back to NZ. But I ended up finding a job here for a year in Wellington. When that was coming to an end, I realised that I didn’t want to be chasing conservation jobs all around the world, but I wanted to stay in Wellington. I found my church community here (St Michael’s in Kelburn) was suddenly the most important thing. The thought of leaving that was quite horrifying. It was quite scary to make the decision to stay based not on financial security—the deciding factor was a network of relationships and meaning rather than those more standard markers of security.

Tell me about your work here at the Alexander Turnbull Library and your career to date

I studied in the UK, and then I got a job here at the Turnbull covering someone’s maternity leave for a year. When she came back, I was expecting to have to find a job back overseas again because there are not a lot of conservation jobs in NZ. But I’d been wrestling with what’s going to shape my decision-making around where I live. It was just before I was baptised as well. I’d decided I wanted to stay in Wellington, but I was panicking about what I was going to do, and I was looking for other jobs. And then I got a word from the Lord, saying, “Just wait until after your baptism. Stop worrying!” So I got baptised and then went away for a week on retreat with a couple of friends. When I came back, on my first day back, my boss said, “Oh, someone else is going on leave; would you like to fill in?” Since then, I’ve been on a lot of short-term contracts, but there’s always been some form of conservation work.

Can you say a little bit more about what your work involves?

My work involves preserving books and works on paper, and occasionally other kinds of objects that have found their way into the Library. There’s two main facets to conservation. One is preventative conservation: managing the environment and the context around materials so that they don’t get damaged or lost—things like relative humidity and light, how things are handled, and how they are stored. And then there’s remedial conservation, which is treating or fixing the items themselves after they’ve deteriorated or become damaged in some way.

Tell us a bit about yourself as a reader. Who are the writers you’ve kept company with across your life, and who has been important for you?

Oh, there’s been so many. I guess even before I could read my parents always read aloud to us, so I was exposed to a lot of writers I might not necessarily have sought out for myself that way. I’d say Terry Pratchett is probably the most constant author because, as I’ve grown, I keep finding more in his writing. On one level, there’s the great story and characters, and the way it’s written; and then, as I’ve gotten older, I realised how insightful he is about humanity and the bigger themes he explores.

My experience of reading has gone through different seasons. When I was at university, it became so instrumental—like, you go to a text and then race through it for something that you can grab out and use. After I finished university, I had to relearn how to wallow in a book without demanding anything in particular of it. You can play with ideas when you’re not trying to control your experience of reading—you’re just enjoying and being curious about all these different things. And then all the different authors you’re reading start speaking to each other in ways that you wouldn’t expect if you’re kind of “I need a quote to support this point that I’m trying to make.”

But I’ve always been interested in people who are writing about spirituality or the divine or God. Who comes to mind? C. S. Lewis: Narnia was quite formative in how I thought about God. And Rabbi (Jonathan) Sacks: I’ve read a lot of his work. I think what I really admired about his writing was he was just so curious—he could draw on all sorts of other writers and thinkers, and they weren’t just other Jewish writers. I found that that kind of openness to what other people have to offer quite rich. More recently, I’ve enjoyed Rowan Williams. Tim McKenzie, my Vicar, gave me three of Williams’s books— Being Christian, Being Disciples, and Being Human—for my baptism.

What led you to study book conservation?

I was studying art history and began to realise that, as much as I loved art history, I really wanted to be working with my hands rather than being an academic. But I didn’t want to be an artist because I was afraid of being poor and not having a steady income stream. And then I found out about conservation through art history, and I thought, “Oh, that kind of combines my interest in the past with something tactile—and, potentially, someone’s going to employ me nine to five to do that.” So it was more the practical nature of the work that really drew me in rather than reverence for the past. But, at the bench, the tactile connection to the past is one of the things that’s most enjoyable about it. Books that are in pristine condition are kind of nice, but they’re a little bit chilly. But then you’ve got books that have been stained or damaged, or they’ve got historic repairs, or they’re actually greasy on the covers where people have been holding them, and that pulls you into an imaginative engagement with the people who’ve handled them before you.

You’ve been involved in the preservation of some early Māori texts. What has this involved? What has it meant for you as a Pākehā?

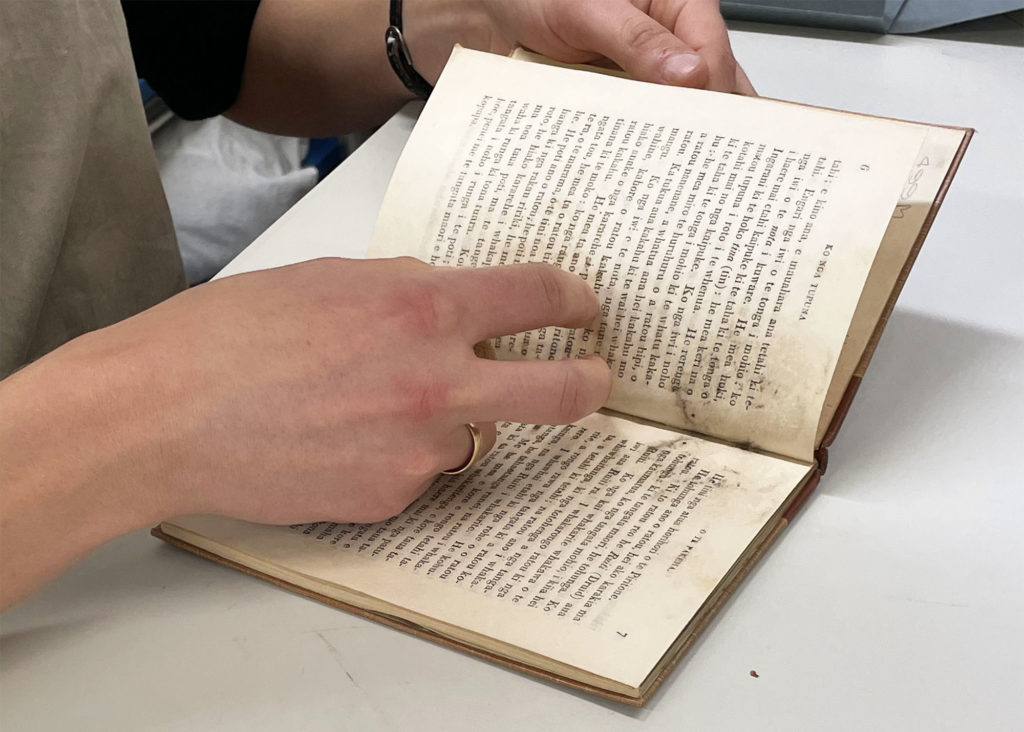

The collection that I’m working with is the Books in Māori collection; it’s based on a bibliography of the earliest printed material in New Zealand up until 1900. The Library’s got a project digitising the collection. My role is checking all the items that are going to be digitised and which ones need treatment before they can be safely handled—getting them ready for digitisation. It also involves rehousing the whole collection: some of it has been stored really well, some of it not very well. So we’re updating all of that. A lot of it is religious material: Scripture, or prayer books, or catechisms. Then there’s a lot to do with the language itself: dictionaries and phrase books. And then there’s Acts of Parliament and things. The types of objects are quite diverse as well. You’ve got little tiny prayer cards and then you’ve got big bound volumes. We’ve got lesson sheets, which are poster size and probably would have been up on a wall. Most of it is little tiny pamphlets that are quite ephemeral in nature.

Looking at these as a conservator, I’m not just preserving the text. The digitalisation is capturing the text and making that accessible, but there’s a whole bunch of information in the books’ materiality, which is something digitisation can’t capture. A lot of them have been hand sewn. Some of them have been stapled, which would have been done by a machine of some kind. And then there’s the ones that are covered in dress fabric. Once you start looking at the material features, you get a picture of the context in which they were being produced as well—the questions of resources and technology, and who’s doing the labour. Some of them are pristine, and some of them are tattered and have been repaired, or you can feel that the paper is softer because it has been handled. All that puts the corpus of texts in their context, and that’s really important.

As a Pākehā, I’ve found working on the Books in Māori collection quite moving, partly because when I was growing up in New Zealand, I never felt like I belonged here. My cultural background did not match that of my friends at school. People always asked me where my accent was from. So I always thought, “Oh, I’ll go back to England and then I’ll feel at home.” I wasn’t particularly engaged with what it means to be a Pākehā in New Zealand because I thought I’d go at some point and not come back. When I did come back and became involved with the Anglican Church for the first time, well, in that context what it means to be Christian in New Zealand was just so overlaid with what it means to be Pākehā alongside Māori in Aotearoa, and so I was having to engage with that in a way I never had before. Because so many of the Books in Māori collection are religious, I feel like this is kind of my ancestry as well in this land—as a Christian, this is a history I’m connected to and have a responsibility to.

Preserving books means preserving the thoughts and writings of a different time and a different place. This might be challenging, especially when you encounter prejudice, condemnation, moral failings, or hypocrisy. Is this a challenge you’ve encountered in your work?

I haven’t ever had an object on the bench in front of me where I thought, “Oh, I don’t want to be working on this.” As a conservator, you shouldn’t be interpreting history for other people (that’s why preserving the original character of the item and documenting any changes made during treatment is so important). I don’t think we should be scared of the past or ideas or objects that have associations that are disturbing or challenging. The uncomfortable feeling itself isn’t a bad thing, and if you don’t ever expose yourself to things that disturb your assumptions about how the world should be, then you never have to grow. I also think if we were to take every bit of material in the library that had some kind of negative association with it and put it in a box and say, “We’ll just not look at this, ever,” you’d get such a distorted view of the past and a distorted view of who we are. Those things are part of our history, and that will have had an effect—for good or bad—on who we are now. If we put that to one side, then I don’t think we can see the present as clearly.

How would you describe God’s interest in your work?

He’s interested in everything! I can’t get away from him in the workplace. More and more, I see the process of being a book conservator as a form of study in God as a restorer and a healer. I didn’t always frame it that way. I started off sort of feeling a little bit guilty about it actually because it was just so enjoyable. I always felt book conservation was a little bit self-indulgent because you’re dealing with things that a lot of people don’t get to see.

But I feel like I’ve learned so much about God through the process of learning how to be a conservator because God is a fixer of broken things. As I treat books, I am sometimes struck by the absurdity: the amount of time and thought and care that I’m investing in something that is possibly more than the effort put into the thing to begin with—lavishing attention on something that sometimes is not very impressive looking.

It has made me think about how God lavishes such care on our lives. I used to think: you learn techniques for fixing x-y-z, and you just apply them to particular problems. But something that works on one item won’t work on another item, and you can’t keep trying to force something to do something it just can’t do—that’s such a frustrating process! And it’s not good for the object! You sort of have to forgive it for being what it is and then work with it as it is. I’m realising that to fix things you don’t just have to understand how they’re broken, you also have to understand where they’re still really good and where they are strong—what has the strength to take a repair. I try more to look at people the way I look at books—responding to who they are, not who I wish they would be. This is all stuff that I know—that I’ve read or people have told me—but something about the tactile experience of book conservation has made it meaningful.

You’re keeping company with these artefacts created by men and women of the past. How do you think God sees them and the times they represent?

It’s a sense of compassion. When you read a book as an object, there are always traces of someone’s life on it—manuscript material, in particular. You see not just the words that have been written but where they’ve been doodling on the page or they cross something out. You get a glimpse into that human being in their day—not the published writer, public facing, but that intimate and slightly haphazard part of their life. Maybe no one else was in that moment of history except God. As a conservator looking at this object, you get a glimpse of it—just the loveliness of the ordinariness of these people.

(Images: Venn Foundation)