18 Jun Four Ways Our Faith Reshapes Our Work

This…is a humble offering to Him.

An attempt to say “THANK YOU GOD” through our work,

even as we do in our hearts and with our tongues.

May He help and strengthen all of us in every good endeavour.John Coltrane – Liner notes to A Love Supreme

John Dennison’s article in this edition of Common Ground completes the third movement in our Theology of Work series, describing how God’s redemptive plan, fulfilled in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, encompasses even our working lives. We are redeemed and restored back into our royal position and our priestly role—free to serve “in every good endeavour”—indwelt and empowered by the Holy Spirit. And God not only sanctifies our work through the completed work of Christ: he continues to sanctify us through our work. Given how much time we spend in our work settings, it shouldn’t surprise us that there are arenas in which Christ’s Spirit can go to work on us—cultivating virtues, challenging vices, and encouraging creativity and imagination.

An author who has helpfully unpacked the implications of this in the trenches of everyday work is the founder of New York City’s Redeemer Presbyterian church, Tim Keller. In his books, Center Church and Every Good Endeavour (a title borrowed from the John Coltrane quote above), he identifies four ways in which our lives of faith should shape and inform our work:

I. Our faith changes our MOTIVATION for work;

II. Our faith changes our CONCEPTION of work;

III. Our faith provides high ETHICS for Christians in the workplace; and

IV. Our faith gives us the basis for reconceiving the very WAY in which our kind of work is done.

It is not intended to be an exhaustive list, but these four simple themes do cover a lot of ground. Given that no resource or programme can outline the exact detail of what being a Christian in every different setting is supposed to look like, keeping these in mind can help create postures that make those details a little easier to prayerfully discern.

I. Our faith changes our MOTIVATION for work

Keller picks out a couple of obvious motivators that the gospel’s reframing of work critiques and corrects. The first is an addiction to power, prestige (or pay!) that would see us chasing those things as ends in themselves … or as identity-constituting. Another way of describing this is with the idolatry language that Olivia Burne drew out in her essay on the folly of Babel—“let us make a name for ourselves.” It is not that money and success are intrinsically bad: many faithful people find themselves in roles that have plenty of both. But our ultimate identity and significance is now found in Christ. Keller reminds us that an idol is simply any good thing turned into an ultimate thing. One way of knowing this is to imagine how easy (or not) it would be to relinquish that thing. If Christ were to say to us, as he did to the rich young ruler, “Give me all … including that …”, could we do it?

Keller’s second point is that our motivations can be misshapen by what others think of us. Paul urges the Colossian church to work “not with eye-service, as people-pleasers, but with sincerity of heart, fearing the Lord” (Col 3:22). He actually coins a new term here—“eye-service”—which literally means “to serve only when someone’s eye is on you.” Although he was addressing slaves (who were perhaps more tempted than most to only work hard when the boss was watching), I’m sure Paul knew that we all have a tendency to be motivated more by publicity than obscurity.

This potential addiction to what other people think of us is a reminder that sometimes work isn’t the central idol; rather, in many cases, it is acting as a middle-man, camouflaging another idolatry that is simply manifesting itself through our work. In his book, The Busy Christian’s Guide to Busyness, Tim Chester helpfully names some potential idols that can masquerade in our work practices:

- The need to prove ourselves;

- The need to meet everyone else’s expectations;

- The need to be in control of everything;

- The need to feel under pressure and useful;

- The need to maintain a certain level of lifestyle; and

- The need to live a full and exciting life.

Again, this list is not exhaustive, nor are the items in it inherently bad—as always, it is the place they have in our heart that matters. But, they’re a good place to start as we close this section with the first of some questions that we might prayerfully reflect on. As we do so, we are reminded that the gospel saves us from these false or distorted ends and frees us to seek work’s legitimate ends: providing for our (family’s) needs; serving others and the rest of creation; and bringing glory to God. And so we might ask ourselves:

- Why am I doing the sort of work/study that I am?

- Could I let it go if God asked me to?

- Why do I work as much as I do? …or as little?

II. Our faith changes our CONCEPTION of work

The first thing we would want affirm here is that Christians should, of all people, have a deep appreciation for the dignity of all work. One way to strengthen that appreciation is to resist the temptation to divide jobs up into hierarchies: “ministry” vs. “secular”; high-paid vs. low-paid; blue-collar vs. white-collar; even cool vs. uncool! Keller gives an example of a young man admitting to that last hierarchy: “I realised that if I stayed in education, I’d be embarrassed when I got to my five-year college reunion, so I’m going to law school now.” This is a pretty hollow foundation on which to build a life of self-emptying service, but perhaps some of our own conceptions and biases are just as questionable. By way of example, Matthew Crawford, a philosopher and motorcycle mechanic (yes, you read that right), offers a brilliant critique of our prejudice towards manual work. As someone with both a PhD and a motorcycle repair shop, he knows better than anyone that the skilled manual trades can be just as intellectually stimulating as working with information and ideas. And yet, he laments, many families continue to view university as the gold standard; apprenticeships are beneath their station. Hierarchy strikes again.

Secondly, this wider understanding of vocation, along with a renewed appreciation for all work, should protect us from the tyranny of having to find the “perfect” job (or the expectation that God provide us with one). “Do what you love for a living, and you’ll never work a day in your life …” I’ve seen that attributed to everyone from Confucius to salsa sensation Marc Anthony—I just can’t seem to find it in Scripture! Tim Chester notes it is a relatively recent phenomenon that Christians would prize intrinsic fulfilment above all else when it came to their work—that is, an internal and personal sense that our work is significant and satisfying. Historically, he argues, it was enough that our work met several extrinsic criteria: “The value of work was measured by the glory it brought to God and the service it rendered to others.” God saw our work and was pleased … and we were pleased because he was pleased. That was sufficient.

Certainly, there are no brownie points to be scored through a false piety that would seek out loathsome work for the sake of it. But there is also every chance that our working life will include (perhaps long) periods of work that seem frustrating, repetitive, dull, and even meaningless at times. Marc Anthony might say those are sure signs to salsa on to the next job! But we march to the beat of a different Caller—and he may ask us to stay and work right where it is most uncomfortable or unglamorous. Once the gospel has softened and subverted some of our hierarchies and misconceptions around work, we are free to hold these options and potential changes lightly. We’re no longer fiercely protecting a brittle sense of identity that is fused to the “importance” of our work. We can face questions like this with a little more honesty:

- Am I carrying a subtle spiritual hierarchy of jobs/tasks in my head?

- Are there any other, equally destructive, hierarchies at play? For example, are there jobs that are beneath me/my (future) children?!

- Am I expecting my job to deliver satisfactions that should be found elsewhere?

III. Our faith provides high ETHICS for Christians in the workplace

Growing up in church, I always got the impression that work was a place where we were supposed to stand out sometimes by awkward attempts to evangelise, but mainly by being kinder and more honest than everyone else. But what do we do when it dawns on us, as it has many times on me, that the “heathens” we are working alongside are actually a lot kinder and more honest than we are?! This is a sure recipe for much distress and discouragement until a more robust Theology of Work reminds us that our efforts are sanctified because we offer them to God in worship, not because we do them with purity and perfection.

Having said that, our ethics do matter. While we would want to critique a Christian understanding of work that reduces our contribution to simply behaving morally, we should also affirm that it should not be less than that. As Keller succinctly puts it: “Many things are technically legal but biblically immoral and unwise and therefore out of bounds for believers. The ethical norms of the Christian life, grounded in the gospel of grace, should always lead believers to function with an extremely high level of integrity in their work.”

Grounded in the gospel of grace: that’s of course what is missing in much of the ethical discourse we hear in workplaces today. There is a compulsory and ever-changing list of occupational, relational, and environmental standards and tolerances to be adhered to. And while we would want to affirm many of them, we also recognise that they can never offer salvation—Christ alone does. And so, to some questions we might want to sit with for a while:

- Are there any particularly complex or “grey” areas in my (future) arena of work?

- Have I noticed any “Achilles heels” in my own life that might make me vulnerable, like pride? Greed? Entitlement? Competitiveness? Am I prone to persuasion or flattery?

IV. Our faith gives us the basis for reconceiving the very WAY in which our kind of work is done

In his book, Making the Best of It: Following Christ in the Real World, John Stackhouse gives a wonderful definition for the biblical concept of shalom, God’s peaceable ordering of things: “A condition in which each individual thing is fully and healthily itself and in which it enjoys peaceful, wholesome, and delightful relations with God, with itself, and with all of the rest of creation.” As the title of his book suggests, we’re not there yet, but it is where we are heading (see Revelation 21–22!) In the meantime, Christ’s resurrection is what N. T. Wright describes as the in-breaking of God’s future kingdom of shalom into the present: “the sign in the present of green shoots growing through the concrete of this sad old world, the indication that the creator God is on the move, and that Jesus’s hearers and followers can be part of what he’s now doing.” The writer of Hebrews describes it as “tasting the power of the age to come” (Heb 6:5). As those tasters, we get, in another of N. T. Wright’s phrases, to participate in pulling some of that future kingdom into the present—partnering with the Spirit of God to discover or develop fragments of shalom in our homes, our workplaces, our churches, and our communities.

So what might those fragments of shalom look like? How might we bring a Christian imagination to bear on our work? Again, it is impossible to be prescriptive as the details will differ for every job and situation. Andy Crouch shares a helpful example—that of his wife, Catherine—in his book, Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling:

In her work as a professor of physics, Catherine can do much to shape the culture of her courses and her research lab. In the somewhat sterile and technological environment of a laboratory, she can play classical music to create an atmosphere of creativity and beauty. She can shape the way her students respond to exciting and disappointing results, and can model both hard work and good rest rather than frantic work and fitful procrastination. …

By bringing her children with her to work occasionally she can create a culture where family is not an interruption from work, and where research and teaching are natural parts of a mother’s life; by inviting her students into our home she can show that she values them as persons, not just as units of research productivity. At the small scale of her laboratory and classroom, she has real ability to reshape the world.

Reshape the world—what a glorious invitation! Even if we only get to do that in “small scale” and largely unseen ways, it’s a glorious invitation. I close with a final couple of questions to prayerfully consider and a similar invitation from Jeremiah to those whom the Lord had allowed to be carried off into Babylonian exile:

- What might “fragments of shalom” look like in my vocational setting?

- How might I bring a Christian imagination to bear on my work?

Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce.

Marry and have sons and daughters … increase in number there …

Seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you …(Jer 29:5-7)

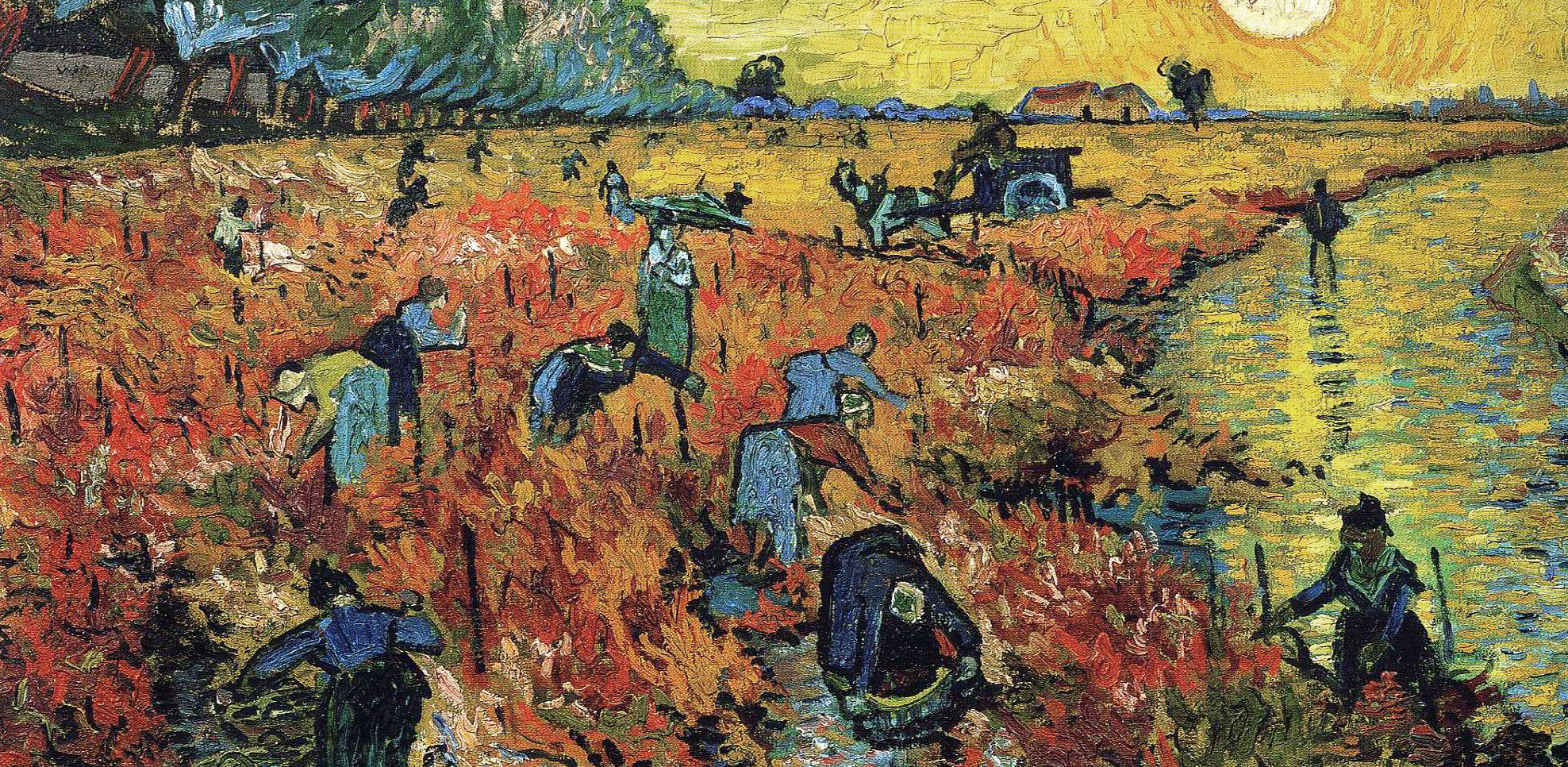

(Image: “Red Vineyard at Arles,” by Vincent van Gogh, Public Domain)