19 Nov The Tremendous Heart of Things

So often we miss it. Harried and distracted, dazed by the seasonal onslaught of tinsel and faux snow and forced cheer—Happy Holidays!—we stumble into Christmas and out again without really reckoning with the meaning of it all: the strangeness, the scandal, the world-transfiguring joy. The Church recognises this risk and has given us the season of Advent to help. Like Mary’s womb, our imagination needs to be prepared to receive the coming Christ; and so, in Advent, we draw on the Church’s storehouses of prayer, song, Scripture, liturgy, and art to make ready our hearts and minds for Christmas.

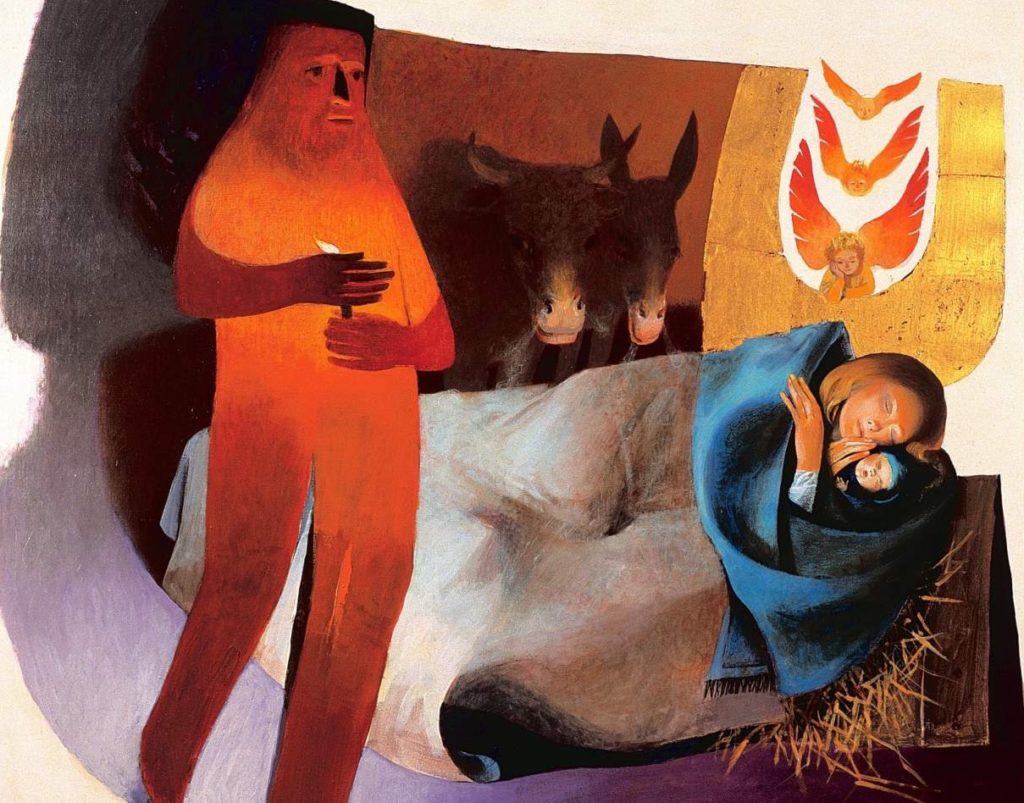

One of my favourite aids in this work of preparation is the painting La naissance à Bethléem by French sacred painter Arcabas (1926-2018). I find much that is pleasing in this painting—Joseph’s strange, orange, almost pressed-plasticine body; the peacock blue of Mary’s cloak; the wispy ghost of animal breath in the morning cold. This painting shows signs of great care and significant thought, and sitting with it helps me to awaken afresh to the mystery and wonder of Christmas. I shake off the tinsel and faux snow; I give over the forced cheer; I slowly begin again to approach the tremendous heart of things.

Consider the child Jesus. He rests under the protective hand of his mother, Mary. Their heads touch. Her finger-tips brush his warm cheek. I imagine she smells the milky, infant scent of him. Let us not lose the wonder of this. Here is God the Son, the one through whom and for whom all things are made—through whom stars and galaxies and seraphim and cherubim and flowers and waterfalls and mountains and bees and particles and atoms and bones and tissue and brain cells and fingertips were made; and here he is, wrapped against the cold in his mother’s cloak. This stable houses the cradle of the cosmos. It is immense with worlds. There is mystery here, to drink in great drafts.

But Arcabas wants us to see more. He has painted around Jesus representatives of all of creation. The donkey and cow, with their warm animal breath, represent non-human creation. Joseph and Mary represent us, human creatures. The cherubim lighting on the window-sill represent the spiritual world of spiritual beings. All eyes are on Jesus. All creation is here united in a common gaze, sharing together the rich, pregnant silence of wonder. Look, Arcabas says: look at what this moment means.

Part of our story, our reality, is that what was meant to be united—heaven and earth, human and non-human creation—is now separated. We live in a world out of joint, fractured. Arcabas wants us to remember that through Christ all these realities are being reconciled, are being brought to wholeness.

There’s a similar scene in Revelation 5. There, representatives of spiritual beings, non-human creation, and human creation gather around the throne of God and praise the Lamb of God for reconciling and redeeming creation. Arcabas is telling us to lean forward, to pay attention—that reconciliation, that bringing of “unity to all things in heaven and earth” (Ephesians 1:10) begins here, in this moment, in this simple stable amidst the animal smells and animal sounds.

Consider, then, the straw. It looks, perhaps, like a crown of thorns. I think Arcabas wants us to hold the incarnation and redemption together in our minds. He wants us to remember where this peaceful, intimate, Christmas-card moment is heading. This child will grow, will step out from under the protective cover of his mother’s cloak, will become a man, and will be put to death, stretched out on the rough wood of a Roman cross—and it is by this death, and the resurrection which follows, that the world will be made right, the broken pieces put back together.

Consider, then, light and dark in this painting. Jesus and his mother are bathed in heavenly light. Behind Joseph is darkness—the outside—but he is walking toward Jesus, his eyes fixed on him. His whole body is illuminated by a candle—a candle that carries a spark of that heavenly light in which Jesus is bathed. There is much here to ponder.

Advent is traditionally connected to themes of light and dark. The gospel writers spoke of Jesus’s coming as light dawning in the darkness. Matthew’s Gospel proclaims, quoting the prophet Isaiah,

the people living in darkness

have seen a great light;

on those living in the land of deep darkness

a light has dawned. (Matthew 4:15-16)

John’s Gospel begins, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it….The true light that gives light to everyone was coming into the world.” Jesus’s coming to Bethlehem is light breaking into darkness. So, too, will it be when he comes again. In Revelation 22:5, we read that in the new creation ushered in by Jesus’s return, “There will be no more night. They will not need the light of a lamp or the light of the sun, for the Lord God will give them light.”

Arcabas invites us to contemplate all this and bring it to mind as we celebrate Christ’s birth at Christmas. The heavenly light, that in this painting is just a window in the far corner, will through Jesus’s life, death, resurrection, ascension, and coming again, spread out and flood all of creation—pushing back the dark and all that it symbolises: chaos, death, suffering, grief, injustice, absence. This is what we celebrate at Christmas: the turning of this great tide, the swell by which we are still being borne into the future.

I too easily forget, and I need to be reminded. Perhaps you do too. Arcabas, I believe, wants us to identify with and imitate the figure of Joseph this Advent season. Joseph’s eyes are fixed on Jesus and wide with wonder. With his cupped hand, he protects the candle of Christ’s light against the pressures and cross-breezes that threaten to snuff it out. He allows that light to illuminate his whole self, until he burns with it as he walks toward Christ, out of the darkness which he is leaving behind. Do likewise, I hear Arcabas inviting me. Do likewise this Advent.

(Image: Arcabas, La Nativité—La naissance à Bethléem, oil on jute, Archepiscopal Palace, Malines, Brussels, 2002)